The Wabanaki

The Nature of PEI by Gary Schneider

Some of you might know that I jointly ran a bookstore in Montague for ten years. The store was misnamed “Idle Hands”—there wasn’t much idleness during that decade. But it reflected my love of books and introduced me to a lot of friends who were also booklovers.

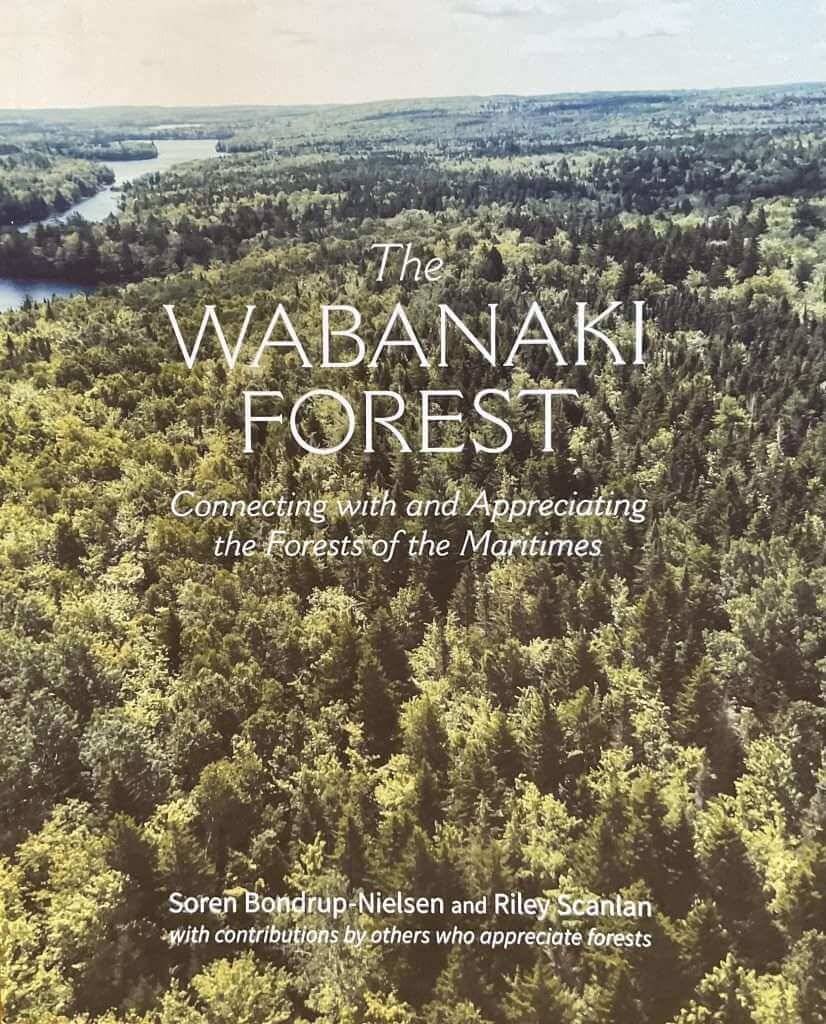

I still have a great fondness for quality books of any kind, but especially ones that help people understand and relate to nature. Recently, I received a copy of The Wabanaki Forest: Connecting with and Appreciating the Forests of the Maritimes and it has been a constant companion over the past week.

The authors have a long history with nature in the region. Soren Bondrup-Nielsen is a Professor Emeritus of Biology at Acadia University, while Riley Scanlan brings their knowledge of and care for forests as a biologist to this work. I had read some of Soren’s previous books but only met him a few years ago. He told me he was writing a book on native forests and I was looking forward to reading it.

I was not disappointed and have added it to my collection of forestry books that are both useful and entertaining—a great combination.

For many years, Soren has been a leading light in the conservation of native forests, educating the public on a variety of issues and being a strong voice for sound forestry practices.

The book contains observations on the state of the Wabanaki Forest. I suspect that both authors wish that they had better news, given how most forests are being treated across the region. But there is still a lot of hope and wonder within the book, giving readers the opportunity to be inspired.

One part of the book that I particularly enjoyed was the focus on understanding and not just identifying. For example, the section on the history of the Wabanaki forest is critical to understanding how we got to our present conditions. If we are to move forward on forest restoration, we need to understand where we came from.

The section entitled “How We See Forests” should be required reading for anyone interested in forests, whether a landowner, a contractor, a provincial forester, or a budding naturalist. We often talk about using science to make decisions. But Soren writes: “The modern world view relies heavily on science’s systematic approach to understand humans, and tends to be unemotional in nature. But tackling the problems facing society today, politically and environmentally, may require a good dose of emotion and other ways of knowing.”

Readers might have crossed paths with some of the contributors to the Wabanaki Forest. Jamie Simpson, a forester and lawyer with several popular books including Restoring the Acadian Forest and Eating Wild in Eastern Canada, writes on his experiences with his own woodlot.

Donna Crossland retired as a biologist with Parks Canada and has been a tireless advocate for sustainable forest practices. Her section on the problems with clearcut forestry details the negative impacts of our most common method of harvesting—that it exacerbates the climate crisis, destroys forest soil carbon, and depletes soil nutrients.

Soren was even kind enough to include a section on “Planting Seeds for Biodiversity,” which I wrote based on my experience with Macphail Woods.

The photos are first rate throughout the book and add a lot to the text.

The authors are generously donating their profits from the book sales to the efforts of the Blomidon Naturalists Society, one of the many great conservation organizations in Nova Scotia.

The book is available at Bookmark in Charlottetown.